Enhance my practice

Here1 you will find tips to help you improve your piano practice and engage more fully in your learning.

______________

1 This deck contains 14 cards and is carefully shuffled each time it is viewed.

→ Move from one card to the next by swiping your finger across the card you see.

-

Attend classes

Attending other students' lessons has many benefits for our piano learning. Thanks to "mirror neurons," when we watch a pianist play, our brain activates in the same way as if we were playing ourselves. This can help us better understand the internal mechanisms that drive our own playing.

Additionally, we can gain a better understanding of certain concepts through the teacher’s repetition, which can present what we already know in a new way.

Moreover, some of our weaknesses are sometimes more evident when observed from a distance. This allows us to address them more effectively.

Furthermore, there are other courses that can captivate us in the same way as piano. Music analysis, music history, composition, conducting, keyboard harmony, improvisation, composition, vocal and instrumental accompaniment, and many others—these courses approach music from different perspectives and provide new and essential insights for piano practice.

-

Engage in physical activity

To further enrich the artistic experience, it is essential to engage in physical activity that promotes movement coordination and strengthens the postural muscles responsible for balance, which is so important in piano practice. It is common to observe that individuals who regularly engage in physical activity approach their instrument more harmoniously, particularly thanks to their posture.

It is therefore recommended to practice physical activity regularly and to focus on the concepts of awareness in movement and a precise mental representation of the body. Various techniques and methods, such as Pilates, yoga, Alexander Technique, Feldenkrais Method, body mapping, etc., support the development of piano technique.

If you experience pain while playing, it is important to respond promptly by taking several steps: seek advice from different musicians and consult healthcare professionals. Beyond treating the immediate symptoms, it is crucial to recognize that pain can arise from an incorrect body representation or excessive focus on a particular part of the body (such as fingers or arms), which conflicts with the notion of inclusive attention, developed by Thomas Mark (2003), who encourages considering the musician’s body as a whole.

From this perspective, embodied cognition (or embodiment), a concept from cognitive psychology, explores the interaction between cognition and the body, challenging the boundary between the body and the “mind.” Work on piano technique can then be seen as an exploration of connections and an inquiry into the boundaries between the musician’s listening, bodily movement, the instrument, acoustics, and the listener’s experience.

References:

JOHNSON, J. (2019). Teaching Body Mapping to Children. Van de Velde.

MARK, T. (2003). What Every Pianist Needs to Know About the Body. GIA Publications, Inc., Chicago.

SCHMIDT-SHKLOVSKAYA, A. (1985). On the Education of Pianistic Skills. Leningrad, “Muzyka.”

Association for Body Mapping Education: www.bodymap.org

-

Take stock

-

Play together

The piano, as a polyphonic instrument, offers a vast and rich repertoire. Its ability to imitate the orchestra gives it a unique autonomy. It is important to consider its metaphorical essence, which lies at the very heart of its repertoire. Indeed, composers often write in ways that aim to express vocal qualities or the specific characteristics of other instruments, such as legato, for example.

To better understand different instrumental and vocal timbres, it is recommended to practice ensemble music, chamber music, and songs or lieder.

Playing with other musicians effectively develops the sense of pulse.

In a chamber music group, it is crucial to achieve a shared understanding of the piece through dialogue with the other musicians. This skill is essential to develop by taking into account the perceptions of others, using precise and appropriate musical language, whether one is a professional or amateur musician, in order to flourish both musically and personally within a collective.

-

Practice journal

Sometimes, you may feel the need to express your thoughts about your progress in a sort of practice journal. Imagine what you might write in one: your reflections on the pieces you are currently playing? The works you hope to perform in the future? Your practice schedule? Your thoughts on your lessons?..

In any case, we invite you to view this notebook as a kind of personal journal, intended solely for yourself and your reflections. It could be a place where you freely express your thoughts and feelings related to your journey as a musician.

References :

Baikie, K. A., & Wilhelm, K. (2005). Emotional and physical health benefits of expressive writing. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment, 11(5), 338-346.

Pennebaker, J. W. (1997). Writing about emotional experiences as a therapeutic process. Psychological Science, 8(3), 162-166.

-

Sight-read

Sight-reading, or deciphering music at first sight, is a practice that contrasts with the meticulous work usually done in piano lessons. Sight-reading can be compared to sketching—a quick and rough drawing made to represent a key idea. Depending on our experience, this sketch may be more or less detailed, but the essence must always be present. Sight-reading is beneficial for musical development for several reasons.

First, this practice awakens our abilities to organize, manage, and prioritize, allowing us to grasp the musical idea as if we were learning to understand meaning by combining letters into words.

Second, by discovering new pieces, we accumulate knowledge about harmonic progressions (cadences, etc.), various compositional forms (lied form, sonata form, etc.), and ways of composing for the piano (scales, arpeggios, chords, etc.). This provides a foundation that makes it easier to approach a new piece.

Finally, this skill facilitates participation in chamber music, enabling us to play with other musicians after only a short time learning a new piece.

It is recommended to practice sight-reading alone or with fellow musicians (pianists, singers, instrumentalists) regularly in order to discover its benefits. There are many sight-reading techniques that can also be applied in specialized classes, such as vocal and instrumental accompaniment lessons.

-

Make steady progress

Piano practice is a complex activity, and like any learning process, it relies on our memory. To improve our skills, we need to regularly review what we have already learned and confront ourselves with new information. Regular repetition helps to better assimilate and memorize it.

Ask your teacher how much time you should dedicate to daily practice outside of lessons. Try to practice every day, even if only for a few minutes, while setting clear and specific goals.

For example: “In 10 minutes, I consolidate the left-hand part by singing it, or in 15 minutes, I learn 2 measures by heart.”

Learning a little every day can be more effective than trying to absorb a large amount of information at once. Indeed, it allows you to focus better on a small amount of material at a time and avoid the fatigue that can result from intensive learning.

Finally, practicing a little every day can help maintain your motivation to play the piano and prevent postponing your practice session.

Download the contract sheet

-

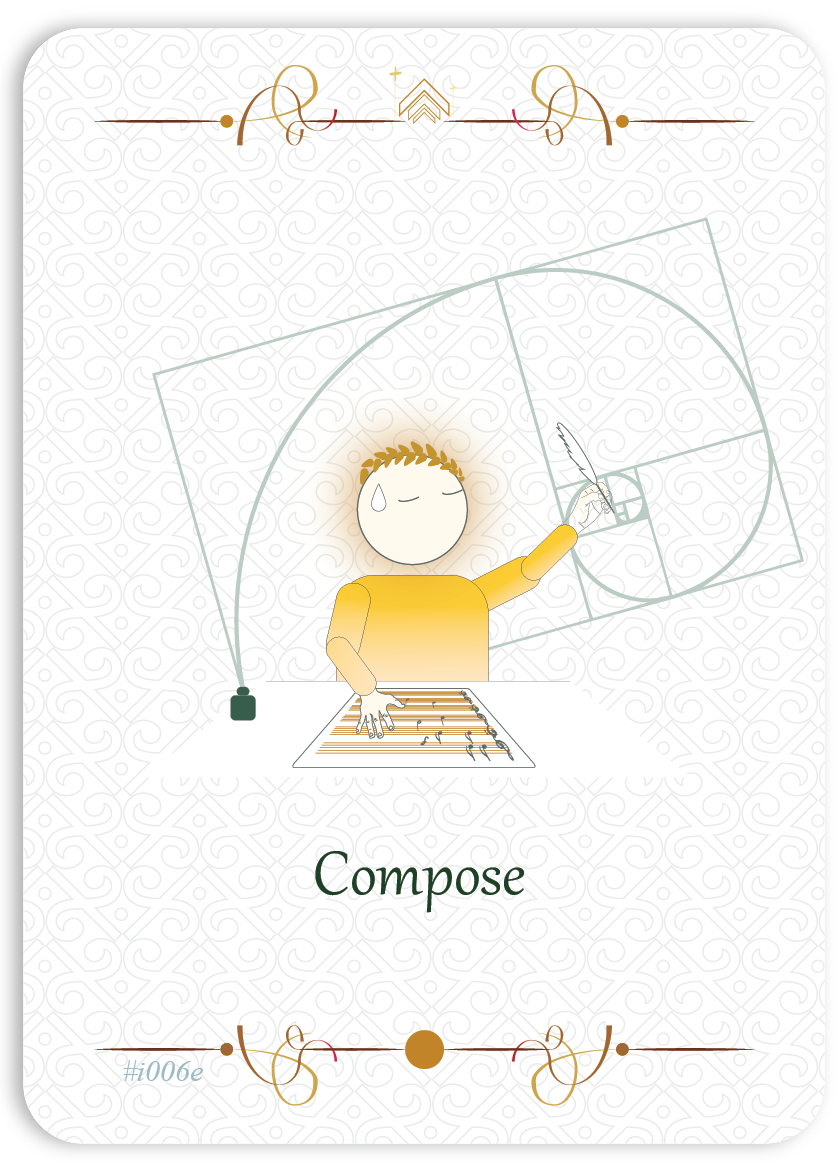

Compose

First of all, when composing, the pianist is faced with handling a variety of knowledge, including harmony, rhythm, form, and more. This practice can help deepen their understanding of music and their ability to communicate it to an audience.

Furthermore, composition can support the development of piano technique, as technical means will be devised by the student according to their expressive goals.

Download sheet music paper

-

Improvise

"Experimentation, when it involves reflection on the fundamentals [...] becomes a means for everyone to discover their ability to express musically their understanding of the world." 1

This beautiful quote from Sylvie Lannes helps us understand that improvisation first appears as a practice of spontaneous personal expression. Its most important value seems to lie in the fact that the framework of this practice (what is allowed and what is prohibited) is established solely by the improviser themselves and stems from their inner will. In this way, it allows us to reflect on what we already know about dynamics, rhythms, harmonies, forms, etc., and thus to learn and develop musically based on the knowledge we possess here and now.

We can improvise alone or with other musicians. Improvisation can take place within a tonal framework and imitate the style of a particular composer. But it can also draw on the writings and playing methods of contemporary music (then referred to as "generative" improvisation). Finally, the notion of improvisation takes on a particular significance in jazz music.

"Free improvisation differs from compositional practices because it is a way of 'experiencing time' that is specific, being 'immediate,' without relying on any intermediary support. It provides the opportunity to experience the rare and rigorous musical concept of a 'time to come' without any operational instructions, referenced knowledge, or pre-determined score dictating the time and space to occupy. Improvising is not 'creating a future object'; it is 'following a path,' individual or collective, grounded in the present—an omnipresent now—while resonating with the past, near or distant."

References:

1 LANNES, S. (2010). Free improvisation attentive to our modernity. In SAVOURET, A. (2010). Introduction to a Solfège of the Audible. Symétrie, Lyon. p.151

SOLOMOS, M. (2019). Electroacoustic musical improvisation: issues and challenges in the development of digital technologies. [Doctoral thesis, University Paris 8 – Vincennes – Saint-Denis]. HAL Open Science.

Critical Studies in Improvisation – criticalimprov.com

-

Watch

Your teacher's advice is invaluable. However, there is a wealth of essential information for your development as a pianist that is difficult to convey through words alone. This is why it is important to learn by observing other pianists play. It is not simply about faithfully copying an interpretation, although this can be a rewarding exercise (widely practiced in other fields, such as painting). Rather, the idea is to focus on the musical choices of the performers and on the movements of their bodies in interaction with the sounds they produce. This observation allows you to explore a wide range of different ways of playing. Regularly watching videos (or attending concerts) is a form of non-verbal learning.

Download the list of pianists and masterclasses to discover.

References:

BREMMER, M. & NIJS, L. (2020). The Role of the Body in Instrumental and Vocal Music Pedagogy: A Dynamical Systems Theory Perspective on the Music Teacher’s Bodily Engagement in Teaching and Learning. Front. Educ. 5:79. -

Listen to music

To learn how to make music, it seems useful to draw inspiration from other musicians. Listen to compositions for your instrument, orchestral works, and vocal pieces to immerse yourself in a variety of works and approaches to performance. This will surely impress you and inspire a greater commitment to your own musical practice.

In addition to discovering the great masterpieces, regularly listening to music informs us about different aesthetics, composers, performers, and their artistic visions. This constitutes a complementary learning experience, equally essential to your instrumental practice.

Psychoanalysts Jean LAPLANCHE and Jean Bertrand PONTALIS describe immersion as a fundamental element of our identities: “Identification is the process by which a subject assimilates an aspect, property, or attribute of another and transforms themselves wholly or partially according to that model. Personality is formed and differentiated through a series of identifications.”

This idea aligns with that of Robert KOZMAN (1991), an educational science researcher. According to him, learning “can be seen as an active and constructive process through which the learner strategically manipulates available cognitive resources to create new knowledge by extracting information from the environment and integrating it into their pre-existing informational structure in memory.”

We can interpret these ideas through the lens of the benefit of listening to music, which strongly influences and shapes our identities as musicians.

Today, we have immediate access to numerous recordings. However, attending a concert or an opera performance offers a unique and immersive experience. We recommend multiplying and refreshing these experiences to enrich your musical practice.

17 works to (re)discover:

MONTEVERDI – Cruda Amarilli (Madrigal, 1605)

BACH – Air on the G String (1717–1723)

MOZART – Piano Concerto No. 23, K.488 (1786)

BEETHOVEN – Piano Sonata No. 23 in F minor, Op. 57, "Appassionata" (1805)

SCHUBERT – Quintet in C major, D.956 (1828)

CHOPIN – Ballade No. 1 in G minor, Op. 23 (1835)

SCHUMANN – Dichterliebe, Op.48 (1840)

LISZT – La leggierezza, S.144 (1845–1849)

BRAHMS – Violin and Piano Sonata No. 3, Op.108 (1878–1887)

DEBUSSY – Rêverie (1890)

RACHMANINOV – Piano Concerto No. 2 (1901)

SCRIABIN – Sonata No. 5, Op.53 (1907)

RAVEL – La Valse (1920)

PROKOFIEV – Piano Concerto No. 2, Op.16 (1923)

LIGETI – Musica ricercata No.7 (1951–1953)

UNSUK CHIN – Toccata (Étude No.5, 2003)

SCHOELLER – Archaos Infinita I & II (2006)

References:

KOZMAN, R.B. (1991). Learning with media. Review of Educational Research, 61, pp. 179–211.

LALAGÜE, A. (2014). Imitating others to become oneself: Imitation as a support for identity. Its contribution to psychomotor practice. Médecine humaine et pathologie ⟨dumas-01018373⟩

LAPLANCHE, J. & PONTALIS, J.B. (1967). Vocabulaire de la psychanalyse. Paris: PUF.

MISSONNIER, S. (2009). Identifications, projections and projective identifications in early relationships: The prenatal score. Le Divan familial, 22, 15–31.

-

Planify

Schedule in your planner in advance the time slots you will dedicate to your daily piano practice and outline the tasks you plan to accomplish. This approach will significantly support your progress!

Sociologist Alfred Schütz views the notion of action as a pre-conceived process (Schütz, 1998). Thus, any action can be seen as the realization of a project. The interaction between these two concepts, “action” and “project,” highlights the importance of planning.

According to psychologist Léandre Bouffard and colleagues (2001), “planning is a mental exercise that prepares action. It encompasses exploring possibilities, identifying means, specifying steps, and anticipating strategies such as problem-solving (D’Zurilla & Chang, 1995), stress management (Schafer, 1992), and action simulation (Taylor & Pham, 1996).”

Furthermore, Gollwitzer (1996) demonstrated that good planning facilitates the initiation and regulation of action, improves performance, reduces stress, and consequently promotes psychological well-being.

We can therefore hypothesize that effective planning also supports piano learning.

References:

BOUFFARD, L., BASTIN, É., LAPIERRE, S., & DUBÉ, M. (2001). La gestion des buts personnels, un apprentissage significatif pour des étudiants universitaires. Revue des sciences de l’éducation, 27(3), 503–522.

D’ZURILLA, T.J., & CHANG, E.C. (1995). The relationship between problem solving and coping. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 19, 547-562.

GOLLWITZER, P.M. (1996). The volitional benefits of planning. In P.M. Gollwitzer & J.A. Bargh (Eds.), The psychology of action (pp. 287-312). New York, NY: Guilford.

LUCANIK, A. (2019). Factors influencing lesson planning: A case study at the American University Institute. Sciences de l’Homme et Société. (Ed. Combe Christelle). Université d’Aix-Marseille.

SCHAFER, W. (1992). Stress management for well-being (2nd ed.). Fort Worth, TX: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

SCHÜTZ, A. (1998). Elements of phenomenological sociology. Paris: L’Harmattan.

TAYLOR, S.E., & PHAM, L.B. (1996). Mental simulation, motivation and action. In P.M. Gollwitzer & J.A. Bargh (Eds.), The psychology of action (pp. 219-235). New York, NY: Guilford.

-

Perform for an audience

Your progress as a pianist will be all the more significant the more public performances you give throughout the year.

All musical practice involves the notion of sharing, and piano practice is no exception. Musicians refine their skills in order to share a rich experience with the audience. If this experience is the ultimate goal of piano practice, it makes sense to organize your musical learning around public performances.

But how can we best prepare for these performances? Should we practice intensively before going on stage? Performing on stage is an extra-ordinary experience (outside the everyday), and the best way to prepare for it is to face it directly. In other words, the more we play in front of an audience, the better prepared we are to perform for one. Therefore, while preparation is essential, it only trains us for solo practice.

It is therefore recommended to structure your learning by multiplying stage experiences according to a simple pattern:

- Preparation

- Several "run-through" sessions in front of a small audience 2–3 weeks before the concert

- The concert itself

In the theory of "typification" by sociologist Alfred SCHÜTZ, we can observe the benefits of performing frequently in public, linked to interactions between past and future experiences: "All the projects of my future acts are based on the knowledge I have at the time of planning the project. It is my experience of previous acts, similar in their typicality to the project, that nourishes this knowledge." (SCHÜTZ, 1998)

References:

SCHÜTZ, A. (1998). Elements of Phenomenological Sociology. Paris: L’Harmattan.

-

Read texts on music

It is important for a student to develop their own relationship with piano playing by complementing their teacher’s guidance with reading on interpretation, the pianist’s body, and the organization of their practice.

Here is a list of books that could enrich piano practice. They are intended for advanced students, parents, and teachers.

CAULLIER, J. (2011). The Art of Interpreting Music: An Essay in Cultural Anthropology. Tumultes, 37, 189–209.

DESCHAUSSÉES, M. (1982). Man and the Piano. Édition Van de Velde.

GAGNEPAIN, X. (2017). From the Musician in General… to the Cellist in Particular. Philharmonie de Paris.

GALLWEY, W. T. (1997). The Inner Game of Tennis. Random House.

KAEMPER, G. (1968). Piano Techniques. Paris: Alphonse Leduc.

MARK, T. (2003). What Every Pianist Needs to Know About the Body. GIA Publications, Inc., Chicago.

NEUHAUS, H. (1971). The Art of Piano Playing. Van de Velde.

SCHUMANN, R. (1848). Advice to Young Musicians.

VARRO, M. (2007). The Living Teaching of Piano: Its Method and Psychology. Proximités, EME.

SCHMIDT-SHKLOVSKAYA, A. (1985). On the Education of Pianistic Skills. Leningrad, “Muzyka.”

Download the bibliography